Golf is a literary sport, perhaps the most literary of all sports. The historical list of great writers is impressive: Pat Ward-Thomas, Henry Longhurst, Herbert Warren Wind, James Dodson, Tom Coyne, Michael Bamberger, are just a few that readily come to mind. Publications such as The Golfers Journal and McKellar have recently made a brilliant effort to restore the literary tradition of the game. There is one man, however, that towers above all of golf literature, the English writer Bernard Darwin.

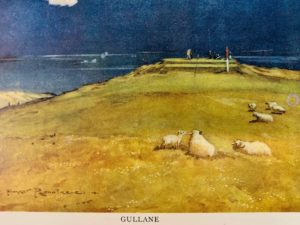

My golf library gives me great solace at times. I enjoy looking at all the books I have collected. Over the past 40 years, starting as a 10 year old obsessed with the game, I have amassed a collection of more than 500 volumes. I have my favorites, of course: James Finegan’s brilliant trilogy of books on the golf courses of the United Kingdom and Ireland, Bamberger’s To The Linksland and Herbert Warren Wind’s Following Through are near the top of my list. However, Bernard Darwin is a writer that I always come back to, time and again. I have 4 of his books in my collection: On Golf, The Happy Golfer, The Darwin Sketchbook and The Golf Courses of The British Isles. Darwin should be read in the Fall, when the sun gets lower in the sky and the temperatures finally start to cool down, perhaps with a wee dram of Springbank (neat). By the fireplace, if you are fortunate enough to have one in your home. This is Darwin writing about one of my favorite places, Prestwick, in The Golf Courses of The British Isles, published in 1910:

“Nowhere is to be found a more beautiful stretch of what is called “natural golfing country.” The ordinary golfer, whose head is not too full of modern architectural ideas, would jump for joy on first beholding Prestwick. There is nothing subtle or recondite about it; it has a beauty which explains itself. There are the great sandhills bristling with bents and the little nestling valleys beyond them, a rushing burn and a stone wall, and it is perfectly clear that man was meant to hit a ball over them.”

Darwin writes with an economy of words that the modern day golf writer would do well to emulate. His style is unique and erudite, yet relatable to the golfer, and always with an underlying dry sense of English humor. His career spanned from the great triumvirate of Harry Vardon, J.H. Taylor and Ted Ray, all of Bobby Jones short career and ending fittingly with his last official assignment covering Ben Hogan at Carnoustie in the 1953 Open Championship. He was a very good amateur golfer in his own right, making the Semi-Finals of the British Amateur twice and playing in the first Walker Cup at the National Golf Links in 1922. No doubt these experiences added to the insight of his writing. Darwin wrote extensively on the great Bobby Jones. Here is what he wrote upon learning of Jones’ retirement from golf at the age of 28:

“The announcement that he meant to retire came as something of a bombshell. We should not perhaps have been much surprised if he had announced it after winning the last of his four championships at Merion, but he made no sign and lulled us into a sense of security. Only the day before it happened I was lunching with two good golfers and we were discussing whether or not he would play in championships again, little anticipating that we were on the point of having our questions answered. We did not all agree. One member of the party thought that he could, and would, play occasionally in championships and take things, by comparison, easily. I held that to do that was inconsistent with his temperament and that he had better take the plunge now at the very climax of his career. It is dreadfully sad to think that we shall not watch him winning our championship again but for myself I am nearly as I can be glad that he has made this decision.”

Can you imagine virtually anyone today writing with this level of eloquence if, for example, Tiger Woods had announced his retirement from golf after his dreadful, zombie-like, Ryder Cup performance? I suppose these are different times and golfers behave much differently now than Bobby Jones did, but I for one would love to read Darwin’s long form written account of the 2018 Ryder Cup. I imagine his insight would be clear, concise and written with an economy that was devoid of any unnecessary drama. If you love great golf writing and golf history, I urge you to try Bernard Darwin.